P a g e 6

G h o s t T o w n s a n d H i s t o r y o f

M o n t a n a N e w s l e t t e r

the company as only western people can enjoy social parties. With all the freedom of western life I have

never seen a man intoxicated at a ball or other social meeting; and the sincere cordiality evinced by the

ladies toward each other would be an improvement on the more cultivated customs of the east.

Between Christmas and New Year the city was unusually lively. The streets were gay with beauty and

fashion, and in the evening merry music and the dance were always to be found under some of the many

hospital roofs of the town. Col. John X. Beidler (then collector of customs at Helena) was here, having a

good time visiting old friends; and Col. Nell Howie (head of the Montana volunteer Indian fighters at that

time) was also among the guests enjoying the festivities of the capitol. We spent many pleasant hours,

during leisure afternoons, hearing Colonels Sanders, Beidler, Howie, Hall and others fight over again the

desperate battles they had had to give in order to make safe the victory over organized crime.

Finally New Year’s morning dawned upon the little mountain capitol, and it was by general consent laid

out as a field day of frolic. A party comprising the heads of church and state—Bishop (Tuttle), chief executive

(Governor Green Clay Smith), Chief Justice (Hosmer), secretary, (Marshal), Professor (Eaton, geological

expert), and some others of us who classed as high privates—started out to inaugurate New Year calls.

We naturally enough first paid our respects to the family of one of the distinguished officials, and found

that our call was not expected. A huge bowl of foaming egg-nogg was set out on the center-table; and we

were made welcome, and accepted accordingly. We spent all of sin hour with the fair hostess, when the

professor decided, from the confusion of tongues, that an analysis of the beverage was a necessity; and,

after a careful and scientific investigation, he reported that the egg-nogg consisted of three gallons of

whisky, one egg and a little cream. I can vouch for the bishop retiring in as good order as he came; but of

the others, including the writer, it is necessary to speak. There was some inexplicable confusion in fitting

our hats as we started, but it may be explained by the very thin air of the mountains flying to our heads.

We did not get over half the city until the walking became very hard for our party, owing to the condition

of the streets and other causes; and it was found impossible to conclude our calls on foot. A few inches of

snow had fallen the day before, and Colonel Beidler, always ready for an emergency, called out a fourhorse

team and sled, in which we completed the New Years calls.

It was not so difficult to get from house to house, but it was very tedious and tiresome getting in and out

of the sleigh so often—so much so, indeed, that several of the party turned up missing on final roll-call.

We had many a song and many a speech and the jingling glasses told of the gushing hospitality that welcomed

the party at every house. The chief justice gave a story and a song and was gravely lectured because

there was no baby in the house. Neither host, nor hostess, nor distinguished guest, received the

lavish compliments of the season that were given to the future statesmen and mothers of the mountains,

now boasting of swaddling clothes. One not yet a week old received the homage of the distinguished party,

as the nurse guarded the cradle with mingled devotion and pride. Several were christened in the

round—not by the bishop in an official way, but in most instances with biblical names.

At last the team was brought up before the hall used by the house of representatives. Colonel Beidler was

sitting with the driver, and, with a merry twinkle of the eye, he said "Fun ahead, boys; let's have a hand in

it;” and he called our attention to a rude placard on the door, stating that a sparring match would come

P a g e 7

G h o s t T o w n s a n d H i s t o r y o f

M o n t a n a N e w s l e t t e r

off at about that time. “All hands come in,” said the colonel; and

he looked especially for the bishop. "Just a little fun in the manly

art,” he added; but the bishop pleaded an engagement, and,

with a kind farewell, he left us.

The legislature had adjourned and the hall of the house had been

converted into a regular ring; the floor was covered with several

inches of sawdust, a circle of rude board seats had been thrown

around the ring, and what I supposed to be a sparring-match was

to be exhibited at the moderate price of one dollar a head. "It’s

to be a square fight, and there will be fun,” said Beidler; but still I

did not comprehend the entertainment to which we were Invited.

After the Orem and Dwyer fight, the legislature had passed a law forbidding public exhibitions of the

manly art, unless the contestants wore gloves—intending, of course, that the heavily-padded boxing

gloves should be used.

Upon entering the hall there was every indication of serious business on hand. A ring some fifteen feet in

diameter was formed and in it were four men. In one corner was Con Orem, stripped to his undershirt,

with an assortment of bottles, sponges, etc.; and by his side was sitting a little, smooth-faced fellow,

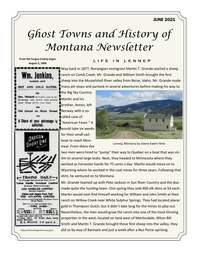

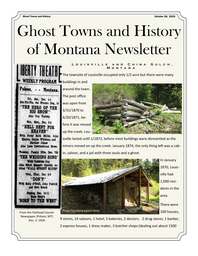

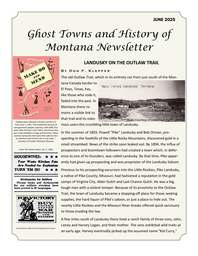

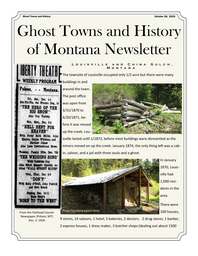

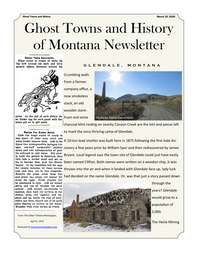

Photo: Richard O. Hickman General Merchandise

building and the Pony Saloon, Virginia City, Montana,

1885. Photographer unidentified, courtesy of MHS

Legacy Photograph Collection, www.mtmemory.org

wrapped in a blanket, looking like anything else than a hero of the prize-ring. He answered to the name of

“Teddy,” although Englishborn, and weighed one hundred and twenty-four pounds. In the opposite corner

was a sluggish-looking Hibernian, probably ten pounds heavier than Teddy, but evidently lacking the

action of his opponent. With him was also his second. He was placarded as "The Michigan Chick.” and

they had met to have a square battle, according to the rules of the ring, for one hundred dollars a side.

Both had thin, close-fitting gloves on and they were to fight in that way to bring themselves within the

letter of the law. Packed in the hall were over one hundred of the roughs of the mines, and I confess that I

did not feel comfortable as I surveyed the desperate countenances and the glistening revolvers with

which I was surrounded. Regarding discretion as the better part of valor, I suggested to Colonel Beidler

that we had better retire, but he would not entertain the proposition at all. “Stay close by me, and there’s

no danger,” was his reply. I had seen almost every phase of mountain-life but a fight, and I concluded that

I would see it out and take the chances of getting away alive. My old friend, Con Orem, who was to second

Teddy, gave me a comfortable seat close by his corner, and reminded me that I was about to witness

a most artistic exhibition of the manly art.

A distinguished military gentleman was chosen umpire, and in a few minutes he called “time.” Instantly

Teddy and Chick flung off their blankets and stood up in fighting trim—naked to the waist and clad only in

woolen drawers and light shoes. Teddy stripped as delicately as a woman. His skin was soft and fair, and

his waist was exceedingly slender, but he had a full chest, and when he threw out his arms on guard he

displayed a degree of muscle that indicated no easy victory for his opponent. "Chick” was leaner, but had

superfluous flesh, and was evidently quite young, as manifest when he put himself in position for action.

He betrayed evident timidity, and was heavy in his movements, but he seemed to have the physical pow